The KGB and Soviet Disinformation

Cover to The KGB and Soviet Disinformation | |

| Author | Ladislav Bittman Roy Godson (foreword) |

|---|---|

| Original title | The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider's View |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Disinformation |

| Genre | Information warfare |

| Publisher | Pergamon-Brassey's |

Publication date | 1983 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Hardcover |

| Pages | 216 |

| ISBN | 978-0-08-031572-0 |

| Preceded by | The Deception Game: Czechoslovak Intelligence in Soviet Political Warfare (1972) |

The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider's View is a 1983 non-fiction book by Lawrence Martin-Bittman (then known as Ladislav Bittman), a former intelligence officer specializing in disinformation for the Czech Intelligence Service and retired professor of disinformation at Boston University.[1][2][3] The book is about the KGB's use of disinformation and information warfare during the Soviet Union period.

Under the direction of the Soviet secret police, Bittman was deputy chief of the disinformation division for Czech intelligence called the Department for Active Measures and Disinformation.[2] In the book, he warns how disinformation can lead to blowback, causing unintended consequences from intelligence agency actions, which were harmful to the Soviet Union.[3][4][5] The book includes case studies of joint disinformation campaigns by the Soviet Union and Czech intelligence and their repercussions, including a successful operation to stop the building of an aerospace center in West Germany and a failed plot to accuse CBS News anchor Dan Rather of murder in Afghanistan.[3][5]

The book received a positive reception from SAIS Review, where it was called "fascinating reading".[5] Foreign Affairs gave a mixed review saying the author exaggerated the role of the KGB.[6] One review in the International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence called the book "an excellent study" and its author "the top authority on disinformation in the U.S.", while another in the same journal said it lacked depth.[7][8] It was also reviewed in the Italian language Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali.[9]

Background

[edit]Ladislav Bittman graduated from Charles University in Prague in 1954 and was recruited by Czech intelligence.[2] He served within the Czechoslovak intelligence agency as its deputy chief of the disinformation division, the Department for Active Measures and Disinformation, from 1964 to 1966.[2][4][5] This division was under the control of the Soviet secret police.[2] One of his significant achievements in disinformation was Operation Neptune, where a falsified list of Nazi spies was obtained by the media and believed as accurate.[1][2] In 1967, he was assigned to Vienna, Austria in an undercover operation as a press attaché, to recruit European reporters as secret agents that Soviet intelligence could use to spread disinformation.[2] He chose to defect to the United States in 1968 at the conclusion of the period known as the Prague Spring, after the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.[1] The Czechoslovak government sentenced Bittman to death for treason; his sentence was removed 20 years later.[1]

Bittman became a professor in the department of communication at Boston University (BU) and began to use the name Lawrence Martin.[1][2][10] While there, Bittman taught journalism with a focus on disinformation at BU and founded the Program for the Study of Disinformation, the first academic center in the U.S. to focus on the study of disinformation.[1][2] Prior to the publication of The KGB and Soviet Disinformation, Bittman had written a book on the history of disinformation in Soviet covert operations, The Deception Game: Czechoslovak Intelligence in Soviet Political Warfare (1972).[11]

Contents summary

[edit]

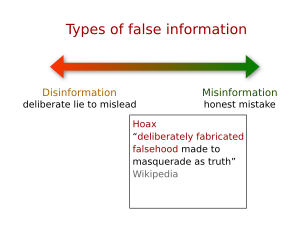

Bittman recounts his time as a Czech State Security (StB) expert at misleading individuals. He describes information warfare tactics used by the Soviet Union, which they internally referred to as disinformation, intended to fool and defraud others. The author defines disinformation as "a carefully constructed false message leaked to an opponent's communication system in order to deceive the decision-making elite or the public".[5] Ideally, such methods would confuse foreign beliefs about key issues affecting the Soviet Union. The author recounts covert operations that significantly affected international relations. Bittman writes that for disinformation covert operation campaigns to succeed, "every disinformation message must at least partially correspond to reality or generally accepted views".[4] In some instances such covert operations led to blowback and unintended consequences from intelligence agency actions, which were harmful to the Soviet Union. Bittman argues such disinformation tactics had the cumulative effect of negative political consequences to the Soviet Union, because its subterfuge campaigns injected false information into society.[3][4][5]

The author recalls a StB operation which began in 1964 with the assistance of the KGB, whose goal was to inflame public opinion within Indonesia and increase negative perceptions towards the U.S. The operation targeted an Ambassador from Indonesia through a honeypot espionage ploy, tempting him with attractive women. The KGB and StB agents were able to turn the Indonesian Ambassador to their interests and through him they passed along to President of Indonesia Sukarno fabricated analyses and false documents, alleging the Central Intelligence Agency was planning to harm him. In particular, a specific false report stated a fictitious strategy supposedly planned by the United Kingdom jointly with the U.S., to invade Indonesia through Malaysia. Another such forgery claimed that the CIA plotted a covert assassination attempt on the Indonesian president.[3]

The KGB and StB ruse succeeded in causing paranoia and the Indonesia president began to make public statements highly critical of the U.S. Reporters within the employ of the two Soviet intelligence agencies promptly capitalized on Sukarno's remarks and incensed the Indonesians with broadcasts of the false reporting on Radio Moscow and groups of angry citizens attacked U.S. buildings in the city of Jakarta. Negative commentary about the U.S. grew markedly within the country at a rapid pace. Perceptions of American interests within the country were decreased to a negligible level, directly due to the Soviet intelligence disinformation campaign.[3]

Bittman recounts other case studies, including efforts by the Soviet intelligence services to influence the views of the Third World against Americans so that such countries would support Russian interests in the United Nations. The author details fruitful efforts of the KGB to stop the building of an aerospace facility in West Germany, after Soviet intelligence fomented false notions that the building was part of a Central Intelligence Agency plot to turn Germany into a nuclear-capable country. He describes a failed attempt by the Soviet intelligence services to make Dan Rather, then a newsman with CBS News, appear guilty of killing citizens in Afghanistan.[3][5]

Release and reception

[edit]The book was first published in 1983 by Pergamon-Brassey's and another edition was released in 1985 by the same publisher, with a foreword by Roy Godson.[12][13] A Spanish language edition was released in 1987 by Editorial Juventud.[14]

Seth Arenstein analyzed the book for SAIS Review and wrote that "Bittman's treatment of disinformation, particularly his meticulous research, makes The KGB and Soviet Disinformation fascinating reading".[5] John C. Campbell reviewed the book for the journal Foreign Affairs and gave a mixed review, "Going well beyond the author's personal experience—he left Czechoslovakia in 1968—the book ranges over the entire field ... with many illustrative cases and items of interest, but also with a tendency to write the KGB's role as larger than life".[6]

The KGB and Soviet Disinformation received both a negative and a positive review in the International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, with Phillips writing "Chez Espionage regulars consider" the book "an excellent study", referring to its author as "the top authority on disinformation in the U.S.".[7] The other reviewer, Peter C. Unsinger, wrote "At times his examination is superficial, and for depth into some specific events, the reader will have to look at Bittman's earlier work".[8] The book was reviewed by Cesare Marongiu Buonaiuti in the Italian-language journal Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali.[9]

See also

[edit]- 1995 CIA disinformation controversy

- Active measures

- Active Measures Working Group

- Blowback (intelligence)

- Counter Misinformation Team

- Denial and deception

- False flag

- Fear, uncertainty and doubt

- Forgery as covert operation

- Information warfare

- Internet manipulation

- Media censorship and disinformation during the Gezi Park protests

- Manufacturing Consent

- Operation Shocker

- Operation Toucan (KGB)

- The Plot to Hack America

- Politico-media complex

- Post-truth politics

- Propaganda in the Soviet Union

- Russian military deception

- Social engineering (political science)

- Persuasion

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Richman, Evan (April 27, 1994), "The Spy Who Came Into the Classroom Teaches at Boston U.", The New York Times

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Butterfield, Fox (November 18, 1986), "Boston U. focuses on disinformation", The New York Times

- ^ a b c d e f g Bittman, Ladislav (1985), The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider's View, Pergamon-Brassey's, pp. 49–52, ISBN 978-0-08-031572-0

- ^ a b c d Boghardt, Thomas (26 January 2010), "Operation INFEKTION - Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign" (PDF), Studies in Intelligence, 53 (4), retrieved 9 December 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arenstein, Seth (1986), "The KGB and Soviet Disinformation, and: Sovieticus: American Perceptions and Soviet Realities (review)", SAIS Review, 6 (2): 224–226, doi:10.1353/sais.1986.0061, OCLC 4894382744, S2CID 153446909

- ^ a b Campbell, John C. (March 1, 1986), "Book Review: The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider's View", Foreign Affairs, 64 (4), ISSN 0015-7120, OCLC 5547492362

- ^ a b Phillips, "The KGB and Soviet Disinformation", International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 1 (3), ISSN 0885-0607, OCLC 12566055

- ^ a b Unsinger, Peter C. (1986), "The KGB and Soviet Disinformation", International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 1 (2): 137–179, doi:10.1080/08850608608435017, ISSN 0885-0607, OCLC 12566055

- ^ a b Buonaiuti, Cesare Marongiu, "Book Review: The KGB and Soviet Disinformation, An Insider's View", Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali (in Italian), 56 (3): 493–494, OCLC 5792426414

- ^ Bittman, Ladislav (1990), "The use of disinformation by democracies", International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 4 (2): 243–261, doi:10.1080/08850609008435142

- ^ Bittman, Ladislav (1972), The Deception Game: Czechoslovak Intelligence in Soviet Political Warfare, Syracuse University Research Corporation, pp. 39–78, ISBN 978-0-8156-8078-9

- ^ OCLC 59067176

- ^ OCLC 443300735

- ^ OCLC 16103979

Further reading

[edit]- Golitsyn, Anatoliy (1984), New Lies for Old: The Communist Strategy of Deception and Disinformation, Dodd, Mead & Company, ISBN 978-0-396-08194-4

- Ion Mihai Pacepa and Ronald J. Rychlak (2013), Disinformation: Former Spy Chief Reveals Secret Strategies for Undermining Freedom, Attacking Religion, and Promoting Terrorism, WND Books, ISBN 978-1-936488-60-5

- Fletcher Schoen; Christopher J. Lamb (June 1, 2012), "Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic. Communications: How One Interagency Group. Made a Major Difference" (PDF), Strategic Perspectives, 11, retrieved 9 December 2016

- Shultz, Richard H.; Godson, Roy (1984), Dezinformatsia: Active Measures in Soviet Strategy, Pergamon-Brassey's, ISBN 978-0080315737

- Taylor, Adam (26 November 2016), "Before 'fake news,' there was Soviet 'disinformation'", The Washington Post, retrieved 3 December 2016

- Nance, Malcolm (2016), The Plot to Hack America: How Putin's Cyberspies and WikiLeaks Tried to Steal the 2016 Election, Skyhorse Publishing, ISBN 978-1510723320, OCLC 987592653

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of disinformation at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of disinformation at Wiktionary

Quotations related to Disinformation at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Disinformation at Wikiquote